Gender Dysphoria: A terrible diagnosis and an even more flawed treatment approach

Gender dysphoria is a deeply flawed diagnosis, but then so are many other conditions that involve the human mind.

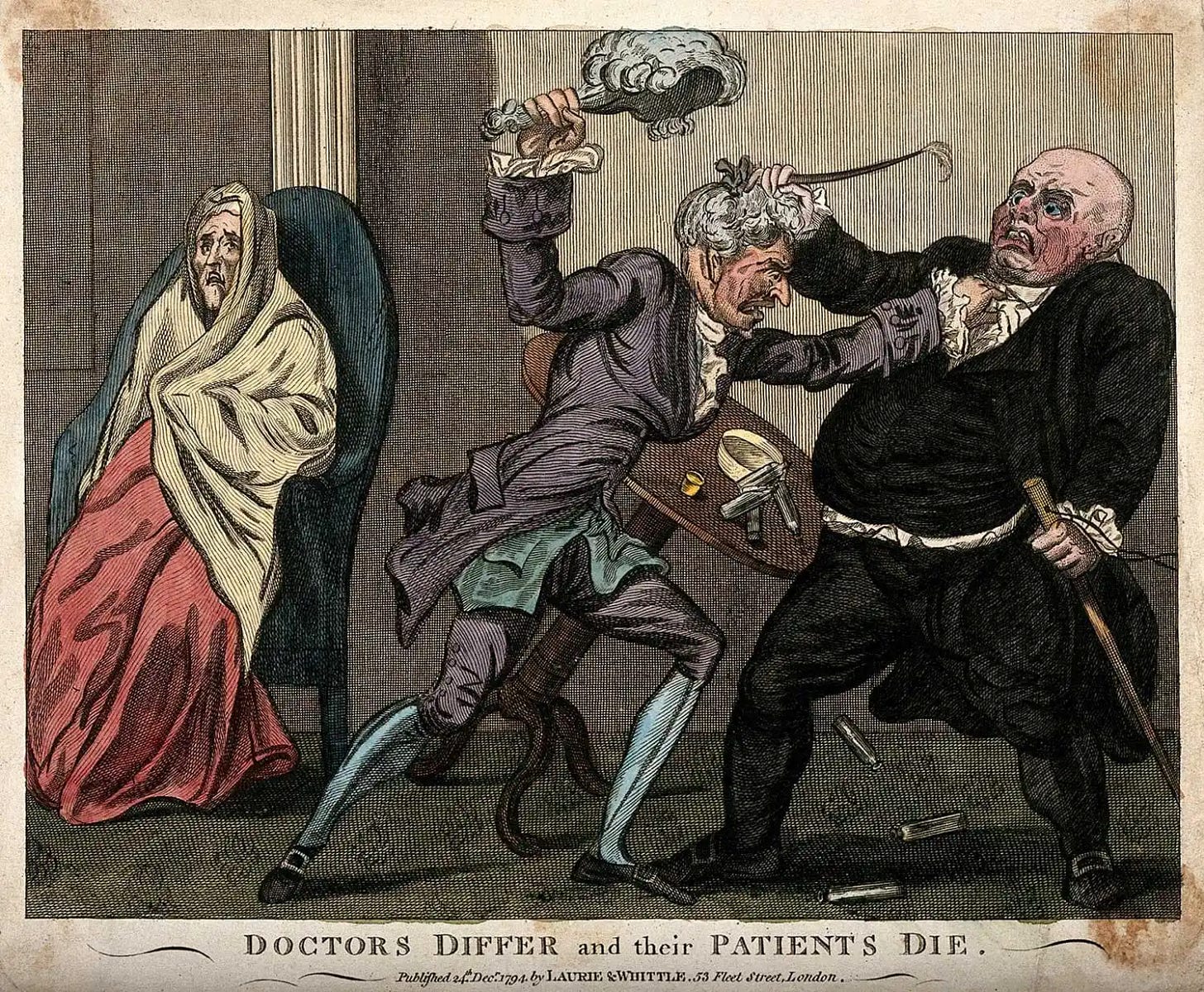

There are certain milestones along the road that can be pointed to as turning points in the trans phenomenon and one of them was in 2013, when the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Edition 5, (DSM-5) changed the diagnosis from ‘gender identity disorder’ to ‘gender dysphoria’. Ray Blanchard, the sexologist who coined the term ‘autogynephilia’ back in 1989, was a member of the Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders Work Group for the DSM-5 from 2008 to 2012 and he recounts the political context in an interview with the National Review. According to Blanchard, the purpose of the change from gender identity disorder to gender dysporia was to get rid of the word ‘disorder’ and this happened “primarily to make patients and also trans activists and transsexual-activist groups feel happy or that they had been listened to, but I would say that the name change probably owed more to — or owed as much to politics as it did to any change in the science.”

Back in 2012, there was no such thing as a ‘gender critical movement’, there were few dissenting voices and so it would have been difficult to stand against this decision. Dissenters at the time believed they had little choice but to leave the organisation as an act of protest.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) publishes the DSM-5, a classification guide for mental health disorders which, in recent years, has shifted from a respected clinical manual to a politically influenced, inflated tome. Sadly, today, rather than fostering a deeper understanding of mental distress, it now often serves as fodder for tabloid critique.

The DSM-5 includes many controversial diagnoses. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), for example, combined several related conditions (e.g., Asperger’s Syndrome) into a single “spectrum.” Many families and advocates argue this was a bad move as it diminishes recognition of unique presentations and potentially impacts access to tailored services. Similarly, there is growing concern about the proliferation of ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) diagnoses, particularly regarding overdiagnosis, misdiagnosis, and over-medication.

In my clinical work these days, all too I often encounter clients who share stories such as, “I was initially diagnosed with ASD, but then a new psychiatrist said it was a misdiagnosis and he diagnosed ADHD. But now I’ve moved doctors again and it turns out that I don’t have ASD or ADHD - I had anxiety disorder all along.” It is difficult to convey the emotional toll and sense of confusion that accompany such a history.

Despite the controversy surrounding the removal of Asperger's from the ASD category, the DSM-5's decision to replace gender identity disorder with gender dysphoria was even more pivotal. This shift marked a fundamental transformation in a niche, under-researched field, reshaping how clinicians approach and understand gender-related distress. When we consider the implications of the word ‘disorder,’ we see how significant its removal from this diagnosis truly was. 'Disorder' implies confusion, a lack of order; in medical terms, it suggests an illness that disrupts normal physical or mental functions, leading to major disturbances in thinking, emotional regulation, or behaviour.

Changing the diagnosis from ‘gender identity disorder’ to ‘gender dysphoria’ has been deeply damaging for many. This shift has led some young people to believe that their primary issue is simply feeling 'dysphoric,' rather than understanding that they may have a disordered mindset causing significant confusion—one that could lead to deep unhappiness unless they take steps to find clarity and consistency. Additionally, ‘dysphoria’ is the semantic opposite of ‘euphoria,’ which brings to mind the strange examples of gender euphoria that are becoming more commonplace.

Of course it’s not just gender dysphoria, ASD and ADHD that are sometimes controversial and/or unreliable diagnoses that sometimes seem to be almost impossible to understand or to measure. Many conditions such as depression, anxiety disorder, body dysmorphia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder, borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, panic disorder and schizophrenia all use self-reporting as part of the diagnosis. Some of these diagnoses are more reliable than others – it is reasonably easy to ascertain schizophrenic behaviour, OCD behaviour and panic disorder. But many of these diagnoses have become diluted by a world that uses these words as descriptors for their sense of passing distress.

These days, many people argue that ‘gender dysphoria’ is not real. And loads of people are averse to anyone using the word ‘gender’ in any context (more on that in a future article!). Yet assessing the reality of certain diagnoses is often challenging—clinicians must rely on self-reports, observations from others, behaviours, and emotional presentations and some diagnoses are inherently difficult to measure. For instance, comparing one person’s experience of ‘depression’ to another’s is nearly impossible. When clinicians rely on self-reporting, as they often do, they have only the individual’s account to work with. Person A might feel paralysed by despair, unable to get out of bed, speak, eat, or sleep. Person B may display a persistently low mood, loneliness, difficulty eating and sleeping, and other common markers of depression. Meanwhile, Person C might appear successful at work, have close friends, and embody outward signs of mental health. Yet, tragically, Person C might die by suicide while Person A and B might recover.

While many might argue otherwise, I believe we have no way of knowing whether a score of 21/27 means the same for me as it does for you when assessing low mood. All we know for sure is that we cannot dismiss a person’s depression simply because they seem to be functioning. As Gerard Manley Hopkins reminds us, “Oh the mind, mind has mountains.”

Psychology and psychotherapy are deeply flawed in that they rely heavily on subjective interpretation, cultural biases, and evolving theories, which can lead to inconsistent diagnoses and treatments. While these interpretive disciplines strive to understand the human mind, the complexity and uniqueness of individual experiences often defy standardisation, making it challenging to create universally effective approaches.

There is no doubt that the current criteria for a clinical diagnosis of gender dysphoria is derisory, whether for children, adolescents or adults, and I urge anyone who hasn’t checked this criteria out to do it now so you can confidently speak about how it relies upon a combination of regressive stereotyping, body dysmorphia and a rejection of the self. As Mia Hughes explained so brilliantly in her presentation at the Genspect conference in Lisbon (this talk will be released on the Genspect YouTube channel this Saturday the 2nd November at 4pm EST) gender dysphoria is an “incomplete, dangerous and practically meaningless diagnosis” and the DSM-5 is“a great work of fiction.”

It turns out that, just like so many other institutions – academia, the mainstream media, and the healthcare system – the trans phenomenon has revealed that the APA (the American Psychiatric Association) and the DSM-5 is rotten to the core. To add further confusion, the World Health Organisation (WHO) doesn’t use ‘gender dysphoria’ but instead chose the term ‘gender incongruence’ in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).

Gender incongruence is defined as a marked mismatch between experienced gender and their sex. Some years ago the WHO moved gender-related issues from the mental health chapter to the chapter on conditions related to sexual health. This move has attracted justifiable criticism, for example, in 2019 Griffin and Clyde asked the following question in World Psychiatry regarding this issue: “We note that ICD-11 has dropped gender dysphoria from its chapter on mental and behavioural disorders, and moved it to the chapter on sexual health. What then, is the exact nature of this sexual health disorder? Are children necessarily prescribed puberty blockers and cross sex hormones because they suffer from sexual health issue?”

As per usual in trans world, everything about the diagnosis of gender dysphoria/gender incongruence is a mess. Nobody knows who or what to believe. This is stressful for everyone as the human brain is hardwired to respond to uncertainty with a surge of anxiety. This stress and uncertainty can lead to arguments as our sense of feeling cognitively itchy makes us irritable and creates an instinctive drive towards certainty – and in this context any type of certainty will do so long as it eases the uncertainty in the mind. This is perhaps one of the many reasons why so many people are at loggerheads over these issues.

However, it could be argued that the issue of differential diagnosis and the conflation of a gender dysphoria diagnosis with 'being transgender' causes even more confusion and distress? And perhaps it would be more productive to focus on improving the current treatment framework for gender dysphoria rather than remaining bogged down in debates over this flawed diagnosis? If we could disentangle the notion that a diagnosis of gender dysphoria must lead to social or medical transition, I believe we could address other conceptual challenges later. Others, of course, disagree, arguing that establishing the correct diagnosis is paramount, as the appropriate treatment path will naturally follow.

Personally, I don't mind—as long as the discussion remains civil, everyone benefits from such debates, as our thinking is sharpened and refined by these challenges. Perhaps the essential question is this: when children and vulnerable adults are actively being harmed, should we first focus on preventing the harm itself, or should we instead address the underlying concepts that create the harm in the first place?

You are such a brilliant writer. So clear, so comprehensive and so deeply helpful. Thank you so much

Very thought provoking, thank you. You concluded with, "should we instead address the underlying concepts that create the harm in the first place?" Yes, that is where I have been going lately. Let's turn the spotlight on why a child or young adult would disassociate with their natural body and disown/remove parts of that body. And let's look at the motives for people or industries who push medicalization with drugs or surgeries.