In 1989, Dr. Ray Blanchard published a paper on autogynephilia—a male’s propensity to be sexually aroused by the thought or image of himself as female. Working at Toronto’s Clarke Institute of Psychiatry from 1980 to 1995—Ontario’s only gender clinic authorized to approve surgical reimbursement—he interviewed hundreds of gender dysphoric males and noticed patterns that previous clinicians had recognized but never properly named.

The breakthrough came when he interviewed a patient who never cross-dressed at all but experienced sexual fantasies of himself as a nude female. That single case made Blanchard realize that Magnus Hirschfeld’s term “transvestism” was “misleading and far too narrow”—it focused on clothing rather than the fantasy of being female itself.

Two types

Through his clinical work, Blanchard identified two fundamentally different groups seeking transition. Homosexual transsexuals—males attracted to males who felt like the opposite sex from early childhood—showed no primary erotic motivation. The second group were autogynephiles, ranging from occasional cross-dressers to those seeking full medical transition, united by what he termed an erotic target location error.

His papers might have remained obscure if not for Northwestern University psychology professor J. Michael Bailey in Evanston, Illinois, who popularized the research in his 2003 book The Man Who Would Be Queen. High-profile trans activists responded with fury, launching a campaign to get Bailey fired. Northwestern conducted multiple investigations that exonerated him, but the personal toll was severe. For Blanchard, watching from Toronto, the guilt was overwhelming: “I felt so terrible. This man, because he liked my work, is having people doing everything in their power to get him fired.”

The activists weren’t random protesters—they were successful professionals living as women who felt “on the brink of total victory.” Bailey’s book threatened to expose the paraphilic basis of their identities. You cannot build a civil rights movement on a paraphilia.

Why trans activism needed children

One puzzle has always troubled Blanchard: why did autogynephilic activists concern themselves with children—the group most likely to mobilize opposition? His hypothesis: hiding autogynephilia required promoting innate gender identity. And if it’s innate, there must be trans children to prove it’s not sexual deviance. This messaging—pushed through schools across North America, media, and books like I Am Jazz—may have triggered what researcher Lisa Littman termed rapid-onset gender dysphoria, teaching vulnerable adolescents that hating your body during puberty could mean you’re trans.

“They could have said, ‘We transitioned as adults after trying everything else,’” Blanchard reflects. “’This has nothing to do with fourteen-year-old girls.’ Why they didn’t, I have no idea.”

The DSM wars and diagnostic shifts

As chair of the DSM-5 Paraphilias Subworkgroup, Blanchard proposed adding hebephilia—attraction to early-pubertal children—to allow more accurate diagnosis. The proposal was killed in a closed December 2012 meeting for “political reasons and guild reasons among forensic psychiatrists.” It wasn’t even relegated to conditions requiring further study. “They just wanted the whole idea killed.”

Meanwhile, the gender identity disorders subworkgroup changed the diagnosis from “gender identity disorder” to “gender dysphoria,” shifting focus from cross-gender identity to distress. Critics argue this was deliberate—if the identity isn’t pathological, only the distress, then the only treatment is medical transition rather than psychotherapy. Blanchard defends the change clinically but acknowledges it occurred within a changing cultural zeitgeist.

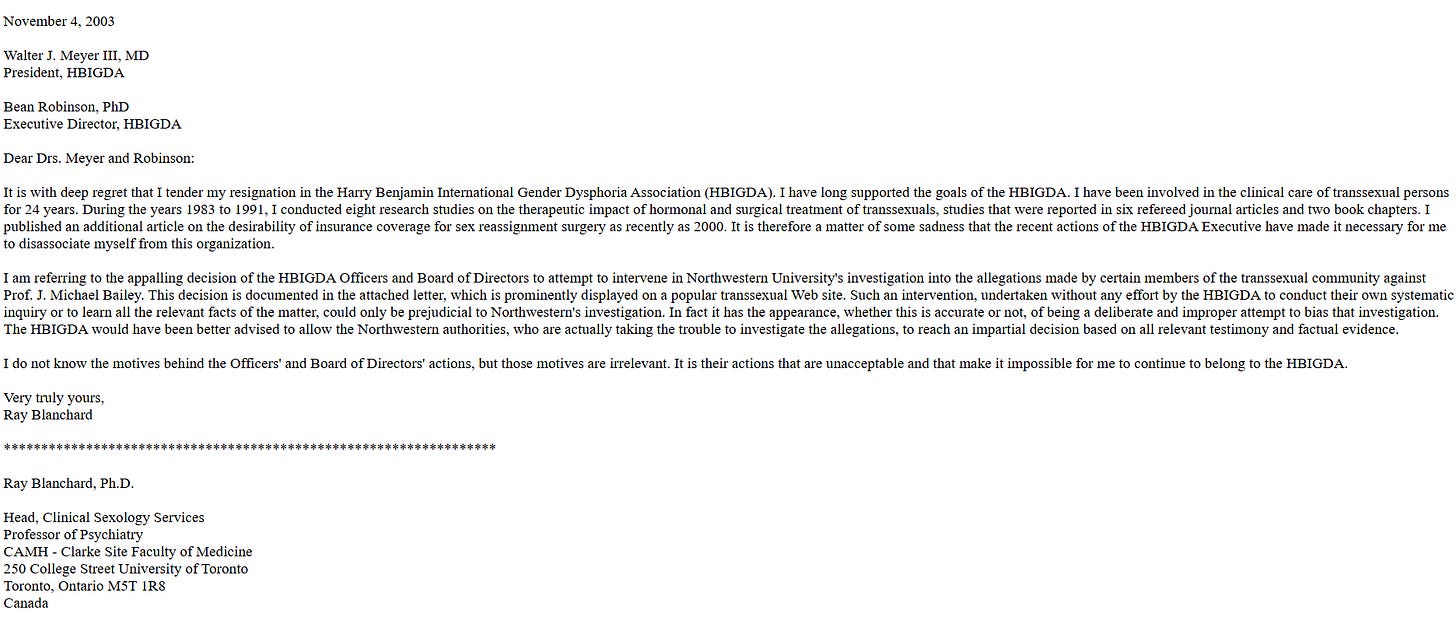

During the Bailey controversy, WPATH (then called HBIGDA) involved itself in investigating Bailey. For Blanchard, this was the final straw. He resigned November 4, 2003, writing in his resignation letter that he was “enraged” at the organization’s interference without knowledge of the circumstances.

The BIID parallel

In 2003, Blanchard attended a Columbia University conference in New York on what was then called apotemnophilia (now Body Integrity Identity Disorder)—the desire to have healthy limbs amputated. He attended a cocktail party at a Riverside Drive home of Dr. Gregg Furth, who had co-authored the 1977 paper with John Money defining the condition. Organizers hoped Blanchard could help establish protocols analogous to gender transition.

He pointed out the crucial distinction: becoming female doesn’t confer disability, while amputating healthy legs does. Conference participants were ready with stories of “differently abled people functioning just fine with only one leg.” He met Scottish surgeon Robert Smith there, who claimed he wouldn’t amputate anyone with fetishistic arousal history—”exactly how people used to talk about sex reassignment surgery.” The irony: Smith had agreed to amputate Furth’s own leg before his hospital in Falkirk shut down the practice.

Blanchard finds the parallel revealing: when you amputate an apotemnophile’s leg, he becomes the object of his desire—an amputee. When you remove an autogynephile’s penis, “he doesn’t become a woman. He still is a man without a penis.”

The research desert ahead

Ask Blanchard about the future of gender research and his assessment is bleak: there won’t be decent academic research for another 10-20 years. “It’s a toxic topic.” He remembers bright students at the University of Toronto approaching with interest in gender identity disorders. His advice was always the same: “You can research some other topic where patients will actually be grateful if you try to help them and you won’t be getting attacked.”

Most universities won’t touch the subject. “Nobody wants a lot of trans activists voting their deans.” While heroic individuals like Bailey continue working, they’re exceptions. The knowledge vacuum will persist until the political climate shifts enough to make objective research professionally viable.

Then and now

The contrast between Blanchard’s era and current practice is stark. His Toronto clinic assessed one patient weekly and approved perhaps ten surgeries annually for most of Canada—”microscopic” compared to today. Patients had to work or attend school as the opposite sex for two years with documentation before surgical approval. In that context of careful selection, some patients achieved better quality of life.

But now? “If this were thirty or forty years ago, I might say, go for it. But you have to understand that now this has become such an issue in society that it might or might not maximize your overall quality of life to transition. And this might seem unfair, but life is unfair.”

The man who named autogynephilia never imagined his clinical observations would become a political flashpoint. After retiring in 2010 from his role as Head of Clinical Sexology Services at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Blanchard watched as his concept became too dangerous to study. His work stands as both scientific contribution and cautionary tale about what happens when paraphilias collide with identity politics—and when medicine prioritizes ideology over evidence.

If you’ve ever felt like something bigger is happening but struggled to make sense of it, Beyond Gender is for you. This podcast cuts through the noise with honest, thoughtful discussions about one of the most pressing topics of our time.

🎧 Watch & Listen

New episodes every Thursday on: